April marks the 160th anniversary of the end of the Civil War, which after nearly four bloody years, consumed an estimated 1.5 million casualties from both sides of the conflict.

It came to a conclusion on April 9, 1865, in the parlor of Wilmer McLean’s house in Appomattox, VA, as generals Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee met in the early afternoon to call a truce.

Ironically, the First Battle of Bull Run took place on McLean’s Yorkshire Plantation, near Manassas, VA, on July 21, 1861. A wholesale grocer by trade, McLean was so terrified by the war that he moved his family to safety in Appomattox to escape the horrors.

By 4 p.m., the surrender meeting had concluded, and as Grant escorted his former adversary to his horse, he removed his hat in tribute, as did Lee.

McLean was reported to have observed: “The war started in my front yard and ended in my parlor!”

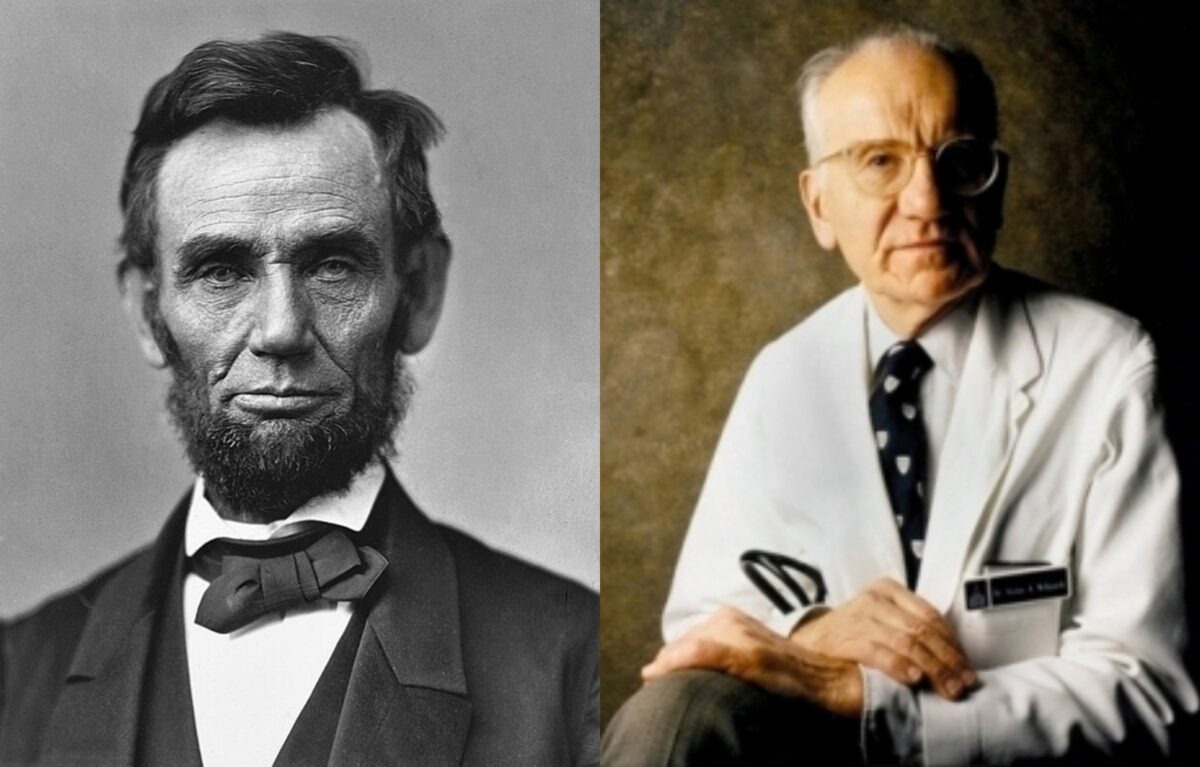

But the celebratory mood that swept the country was soon shattered by an assassin’s bullet days later on April 14, as actor John Wilkes Booth fired his Deringer into President Abraham Lincoln’s brain, as he and his wife sat in the presidential box with friends in Washington, D.C.’s Ford Theatre watching a performance of Our American Cousin.

“Lincoln never knew what happened to him,” wrote author James L. Swanson, a Washington attorney and Lincoln scholar, in his 2006 book, Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln’s Killer. “His head dropped forward until his chin hit his chest, and his body lost all muscular control and sagged against the richly upholstered rocking chair. He did not fall to the floor.”

Mortally wounded, Lincoln was carried across the street to the home of William Petersen, where he died the next morning at 7:22.

One hundred and twenty-six years later, in 1991, Dr. Victor A. McKusick, professor of medical genetics at Johns Hopkins, who was known as the “father of medical genetics,” and an acknowledged expert on Marfan syndrome, was selected to head a DNA Advisory Panel investigating Lincoln’s death. The committee was composed of medical experts, historians, and Lincoln scholars who sought access to Lincoln’s preserved DNA—which consisted of hair, bone, and blood, for study.

“Marfan syndrome is an inherited genetic [connective tissue] disorder characterized by long limbs, sunken eyes, and quite possibly life-threatening issues,” reported The Baltimore Sun at the time.

A clinical diagnosis of Marfan syndrome in a 7-year-old boy who had a common relative in Lincoln’s paternal great-grandfather had been made back as far as 1964, according to a 2007 article in the Cleveland Journal of Medicine.

“I think there’s a 50-50 chance that Lincoln did have Marfan syndrome,” McKusick, who passed away in 2008, told The Sun.

It was his contention until his death, had Booth not killed the president, he would certainly have succumbed to Marfan’s.

The last meeting of the DNA Advisory panel was in 1992, when the study of Lincoln’s DNA was denied by various institutions for a variety of reasons, including violation of Lincoln and his descendants’ rights to medical privacy.

Suggesting that a study of the president’s DNA would be useful in treating Marfan patients in the present day, McKusick pressed on, but to no avail.

Interestingly, Booth’s descendants also had questions surrounding his remains in the mid-’90s.

After carrying out the assassination in 1865, Booth and his accomplice, David E. Herold spent 12-days zigzagging across Southern Maryland as the largest manhunt in American history unfolded. They were eventually caught and forced to surrender in the Garrett farm not far from Port Royal, VA.

On April 26, Col. E.J. Conger of the U.S. Secret Service and troops of the 16th New York Calvary ordered the two men to surrender. Herold fled the barn while Booth remained behind as Conger warned him the barn would be set on fire.

“Withdraw your men a hundred yards from the door and I will come out alive,” Booth screamed as the fire roared in its intensity.

The assassin was felled by a single shot from Sgt. Boston Corbett’s carbine that left a devastating wound as it tore through his neck and spinal column. As he was dragged from the inferno, Booth begged, “Kill me, kill me!”

Herold was later executed on the gallows at Washington’s Arsenal Prison two months after Lincoln’s assassination, while Booth’s remains were placed in a musket crate and buried in unconsecrated ground of the Old Arsenal penitentiary, where he lay until 1869 when President Andrew Johnson ordered the body to be released to his brother, noted actor Edwin Booth.

Booth’s body was then taken to Baltimore and the Fayette Street funeral establishment of John H. Weaver—only a few doors away from the Holliday Street Theater where Booth had experienced many of his theatrical triumphs.

On a late June night, preparations were made for Booth’s burial in the Booth family plot in Green Mount Cemetery, where he was led by an eerie small torchlight procession to his final resting place.

The graveside service was performed by the Rev. Fleming James, an Episcopal rector from New York, who had been visiting Baltimore. (When his parishioners discovered he had presided over the funeral for Lincoln’s assassin, he was immediately fired.)

The remainder of Edwin Booth’s life had been overshadowed by his brother’s infamy, and when pressed why the grave was unmarked, he replied, “We’ll let that remain as it is.”

In a final bizarre turn, a 1995 lawsuit was brought before a Baltimore Circuit Court judge by descendants of Booth seeking to exhume his remains from Green Mount Cemetery.

The basis of their inquiry was to determine if the body buried there was really his, because for years, it was rumored that Booth had survived and lived in the Southwest, and that after his death, a mummified body that had become a carnival sideshow exhibit was that of the assassin.

The hope was that DNA from the body would be compared to that of living descendants.

The judge ultimately refused to authorize the exhumation.

Frederick Rasmussen is a Baltimore journalist who previously reported for The Baltimore Sun and The Evening Sun for 51 years, most notably as an obit writer for the publication since the 1990s.